Innovation is the skill of going from idea to action. If innovation is low, ideas risk getting lost or discarded and you risk missing out on great opportunities.

As a tech organization, how do you make sure that you are innovating? In my opinion, innovation doesn’t “just happen”. It’s part of Creative Management. While the dream scenario is that any engineers can propose an idea to work on within their team sprint, I have seen multiple reasons why this fails:

- “There is no time for that.” Teams working under urgent conditions might constantly down-prioritize trying out new things.

- “Could you explain why we need to do that?” This is a common question you might get if the stakeholder is choosing what you should work on during your sprint. Sometimes innovation comes from crazy projects that are hard to argue for.

- The team might lack psychological safety to allow for ideas to bubble up.

- The team might lack an understanding for the process of trying something new.

- Planning for innovation kills innovation. This is a big one for me. I just don’t feel as creative if I need to explicitly ask for permission and plan for innovation. I am the most innovative when I sometimes stumble across a small problem and immediately can spend time finding a solution.

So, if innovation is hard to get into the regular planning with the team, how can we increase innovation? Here are some tools that I have seen successfully deployed to help with this:

The “three-bucket model” for individuals Link to heading

I’ve previously written about the “three buckets model” for individuals. By making it explicit that there is a “me bucket”, I have implicitly allowed myself and others to take the time to try out something without having to ask for permission.

The three categories of work for teams Link to heading

In the article “Three categories of teamwork” I wrote about a model where team tasks are sourced from three categories: Product Asks, Operational Work, and Team Initiatives. Explicitly sourcing tasks from “Team Initiatives” help the team to start thinking about improvements they can make. It also signals that innovation is not someone else’s job, but everyone’s job, including engineers.

Hackathons Link to heading

Hackathons are usually larger events where an entire department comes together to build something rapidly and collaboratively. People form teams of ~2-5 people and work on a chosen project. The hackathons I’ve taken part in lasted for at least two days. Usually, the hackathon ends with an event where all the hack projects built are presented. The only rule is that all teams need to present what they built so far during the hackathon at the end.

An optional additional rule for a hackathon is that everyone must team up with at least one person from another team. I have seen firsthand that this is a great way to foster cross-team collaboration and connection building.

Some hackathons I have participated in had competitions involving prices for various categories. Of course, you can have fun prices such as “the cutest innovation” or “the funniest hack”. However, I am generally hesitant to introduce themed prices for innovations since it adds constraints to the projects people take on. I have seen some remarkable things come out of hackathons - and it’s usually never the improvements I was expecting (new deployment tools, scripts to debug more easily, a brand new product feature). Adding constraints can harm the innovative outcome. You can have themed hackathons, though. They are useful if you would like to innovate on a specific topic.

Hackathons can also be had across an entire company and not just within an engineering department. This is cool! Imagine all the helping hand an engineer could give the legal, HR, or marketing department. I have seen great process improvements come out of it; Create a website for hiring? Or help the legal department search through contracts faster? Or configure Google Analytics to help the marketing department understand visitors better?

Hack days Link to heading

Hack days are micro hackathons, but on a smaller team basis on a regular cadence. Usually, a hack day happens at least once per month, but I used to work in a team where we had one every two weeks. Similarly to hackathons, the only rule was that you presented what you had done for the day.

The outcomes from our hack days included everything from “fixing that bug you never got to” to “trying out a new programming library to learn something new”.

I have also seen variations where hack days are incorporated as part of the larger ritual of a team. Some teams do a hack day at the beginning of a sprint. Basecamp’s Shape Up has a “cool down” period at the end of each cycle which is a little similar (but lasts multiple days).

Tech Show’n’tell Link to heading

Tech Show’n’tell, also known as Tech Demos, is a place where engineers come together to celebrate innovation. They are regular events where engineers and teams share what they have built, tried, or learned:

Built can be everything from a small tool, a proof of concept, or a fully functioning product feature.

Tried can be things like experiments, but also team processes or tools. Maybe a team is trying out mob programming and would like to share their learnings with the rest of the organization. Or maybe a team discovered a new wiki SaaS they are trying out. Tech Show’n’tells are not just to show techie things.

Learned can be things someone learned by reading a book or a blog post. Maybe someone learned the different types of test doubles? Or someone did do some research around testing frameworks and wanted to share their learnings?

Create a knowledge-sharing water hole Link to heading

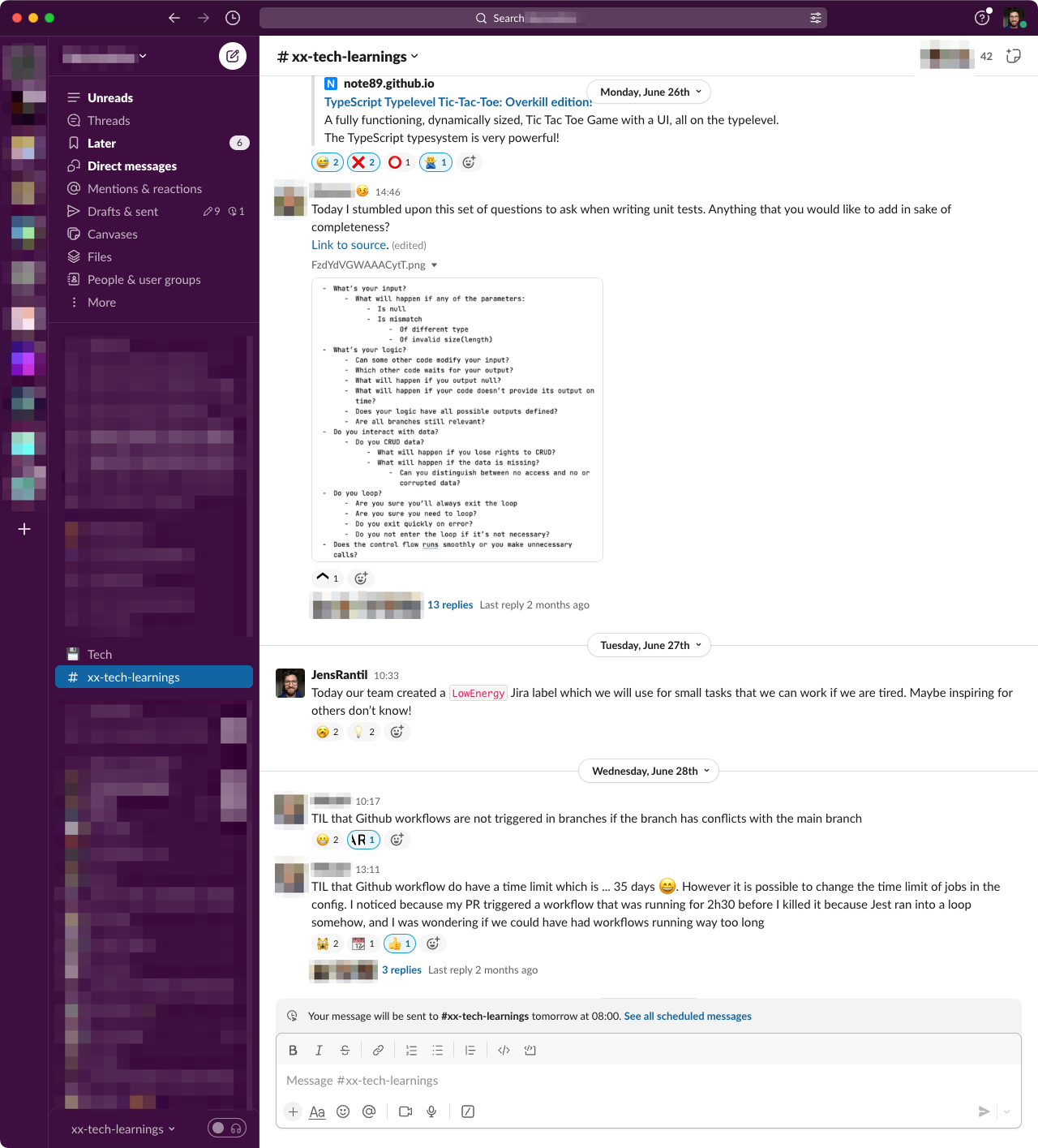

Innovation happens easier if you create an environment where ideas and

knowledge can flow. I love creating “water holes” - places where water cooler

conversations can be had around certain topics. A #knowledge-sharing chat

room (Slack channel, etc.) can be a surprisingly simple way to increase

knowledge sharing.

Create an RFC template & process Link to heading

An RFC is also known as “Design Document” or “Project Document”. I think the article Design Docs at Google explains the concept much better than I ever will. Having a template for this can be useful to create a common structure when pitching an idea.

Remember, though, that a template isn’t all. You need a clearly defined process for how the process on where to share/pitch an RFC, how to resolve disagreements, who has the mandate to decide on, or reject, an RFC, etc. This might or might not be documented in the “I have an idea!” document mentioned in the next section.

Creating clear innovation processes Link to heading

A common question I have heard engineers ask is “What should I do if I have an idea?”. It’s not always clear! The answer depends on

- Ways of working. Basecamp’s Shape Up framework has built in pitches. Other companies have quarterly OKR/OKD planning periods. Certain teams have ticket refinement sessions.

- Where ticketing systems exist.

- Company culture. For example, do you have a flat hierarchy that allows engineers to reach out straight to the Chief Product Officer or not?

- And more.

If it’s not clear where to direct ideas they are dropped and become missed opportunities.

At my two previous employers, I have created an internal guide called “I have an idea!” where I have explained what actions engineers should take if they have ideas. What to do depends a lot on what type of idea. Depending on if you come up with a completely new business idea vs. a small UX improvement has a big impact on where to go next! On a high level, my document has included different recommendations based on different scenarios. The scenarios usually include

- “I have an idea with a concrete solution.”

- “I have an idea for a small improvement.”

- “I have a larger product idea.”

- “I have a UX improvement.”

For each scenario, I’ve presented recommendations on what people could do. These include things like

- Demoing the idea/solution

- Building a proof-of-concept

- Submitting a pull request and asking for feedback from peers

- Giving a presentation

- Pitching to a team (on Slack, or in a meeting)

- Pitching to a tech lead or manager (on Slack or in a meeting)

- Writing an RFC

- Submitting a ticket

- Asking a manager for help

Which recommendations you give depend on your company’s ways of working.

By having an “I have an idea!” guide you help people on what they should do when they have an idea. Without such a document it is not always clear where to take ideas and there is a risk you lose out on innovative ideas.

Reducing processes that kill innovation Link to heading

Finally, removing rigid processes can be a great way to create innovation. If you prefer toolkits over rigid processes you increase the likelihood of engineers naturally coming up with better processes or finding better tools to do the work they need to do. Remember that it is usually, the builders (your engineers) who know which tools and processes they need to have in place to do their job best.

Closing thought Link to heading

Innovation is not just something that “happens”. It is something that you actively need to create spaces for if you want to take it seriously. I hope you and your team will find any of these tools useful or inspiring.